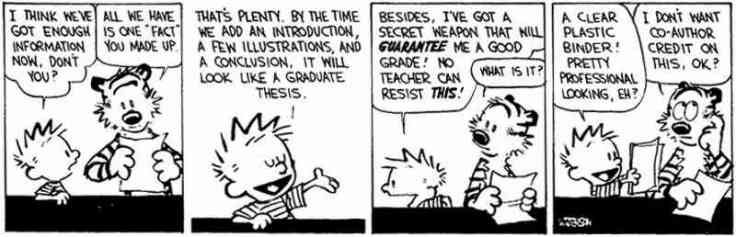

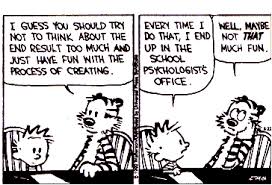

With deepest respects to Bill Waterson, but when that title image is literally the FIRST thing to come up when I Google ‘Conflict’ I can’t pass it up. (Not to worry Mr. Watterson, I’m quite certain I’m not making any money off this particular post – but I would happily accept the opportunity for someone to make a liar out of me…)

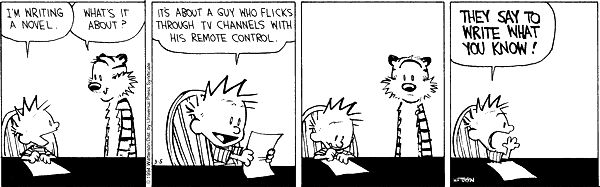

And yes todays title is a riff on the ‘STAR TREK: Discovery’ episode 4 title “Context is for Kings” but I will save what I have to say about DIS for my long awaited treatise on the new show to be published tomorrow. We’ll talk all about screenwriting again today, or at least as much as we can before I realize I’ve run out of things to say. Maybe we’ll even tie in as many Calvin & Hobbes shout-outs as we can.

There’s always a bunch of lessons screenwriting books and online tutorials and quick-reference cheat-sheets want to teach you – and I’m going to repeat one of those now myself! Drama is conflict. Conflict is story. Story is what you do, so you’d better be comfortable mastering ‘conflict’ in your scenes if you want to be any good at this. “Well no shit dude, that’s like literally screenwriting 101.” you say to yourself as you stop reading my blog post. Fine, go ahead. Leave. Whatever. I don’t need you. I’m gonna write about ‘Trek tomorrow and get a million views and spend the rest of the week arguing with other nerds about whether or not Klingon’s shaving their heads is canon.

If you ARE still here though – well damn, now I gotta actually try and be insightful and entertaining all at the same time. Ooof. Okay – CONFLICT! Yes, drama is conflict, and conflict is what makes things interesting, otherwise the tales you tell are just people sitting around agreeing all the time and that’s not interesting at all (in this day and age it also seems a little like science fiction – people AGREEING with each other? I don’t even know what that looks like anymore…)

Across dramatic mediums there are plenty of ways to approach confict – since I’m a screenwriter we’re going to stick with that format today though, because I can speak with a touch of authority there.

I’ve filled this space before with reference to my conversation with another writer regarding drama and screenplays, where this ubiquitous Sorkin quote always emerges:

“Any time you get two people in a room who disagree about anything, the time of day, there is a scene to be written…”

And really, who am I to disagree with A-Sork? I won’t – but my classic counter to that quote is one I’m hoping will show up in a screenwriting text book one day:

“Sure, but then you take those two people, you put them in a plane and set the plane on fire and now you have a movie.” – me (I hope)

Not here to disagree with an Oscar/Emmy winning writer, but I think we both have valid points. Let’s try a different anecdote to put things in perspective. Working on the show out here we spend a great deal of time ‘breaking’ the outlines – figuring out where we need to get our characters by the end of the episode, what beats they need to hit and what developments we need explore in order to push the plot forward. Difficult as it sounds that’s pretty much the easy part. Once we have those basic outlines we start moving off ‘story-arcs’ and into ‘scene breakdowns’ where we figure out how each little bit proceeds into the next. Yes, essentially every TV writers room works like this, and there’s a reason for it…

This process lets you see where everything is progressing, and shines a light on the most important part of your story – the conflict.

“Okay, so in the outline we have our characters find the giant space-whale and climb in his mouth so they can travel to the glass palace on the moon. Check!” *

“Is that like it though? They just climb into the whale and head to the moon?”

“Yeah, that’s where we need them to be for the ACT V out. I mean dude, did you miss the part where I said IT’S A SPACE WHALE THAT FLIES TO THE MOON? Isn’t that ENOUGH for you, sinister task-master?”

“It just feels kind weak is all. Like can one of them NOT want to get into the whale, and then the others have to convince them? Maybe he’s afraid of whales because his Father used to read him ‘Moby Dick’ as a bedtime story while dressed like Pennywise?”

Boom! All of the sudden you’ve taken your boring ‘space whale’ development and made it more interesting by finding the conflict among characters. Even the most wicked-cool developments need some drama in order to be compelling, otherwise they become nothing more than cool concepts/images on screen, rather than an actual story.

It happens every time we reach a scene where the conclusion arrived at is: “This isn’t working.” – “We’ve got our characters to the glass moon palace now, and they go inside and kill the fat, blue moon-wookie, but it’s just not landing. It feels too easy.”

“Maybe someone wants to side with the fat, blue moon-wookie, or thinks they shouldn’t kill him because he’s the last fat, blue moon-wookie of his kind.” If it doesn’t feel right, or if people aren’t engaged, look for conflict.

I have a kick-ass low budget indiefilm screenplay I’m working on about two loser best friends who make an ill timed trip from Northern BC down to Vancouver to see their favourite DJ, and the complications that ensue when everything that CAN go wrong for them DOES. Guess what though? In all of my re-drafting out here I’ve discovered that when I’m not throwing obstacle after obstacle in front of this dynamic duo, the scenes I have of them interacting are a little flat. Sure they share rapid fire, witty dialogue back and forth like I’m trying ‘out-Smith’ Kevin Smith, but there’s nothing substantial which drives the plot between THEM. As fun as it would be to watch these two bounce witticisms about the meaning of life off each other, it makes for poor drama.

So I went back to my deepest influences to learn how you put sweet, dear best friends in constant conflict with each other:

There is no question in anyone’s mind that Calvin & Hobbes are the very best of friends – yet they agree on almost nothing and spend most of their time antagonizing each other. This is how good drama NEEDS to work, and it’s something I’m paying more and more attention to.

There’s another example we can use:

I should really start using references that aren’t 30/40 yrs old…

Anyone who’s visited my site (Thanks to both of you) knows M*A*S*H still has a huge influence on me today. When talking about ‘conflict’ it’s rife with excellent examples of both good ways to achieve it, and places where they missed the mark. In the early seasons we had Hawkeye & Trapper, two nut-jobs doing their best to combat horror with comedy. Their interplay was hilarious, but they were very much ‘two peas in a pod’, both madmen on the brink. The primary conflict came from their interactions with the characters around them. Once Trapper left (to star in his own short lived TV show…) Dr. BJ Hunnicut arrived and the Hawkeye + sidekick dynamic changed. BJ was still an irreverant jokester for sure, but he was far more ‘moral’ and grounded than Trapper ever was.

What had been two frat boys making a mockery of those around them turned into a deeply satisfying comedy routine, with BJ playing the ‘straight man’ to Hawkeye’s antics. The difference in their characters, the conflict created by Hawkeye’s brand of nihilism-lite contrasted to BJ’s ‘family values’ elevated the drama and discourse of the show in a way the Hawkeye/Trapper dynamic never could. It was rare that Hawkeye & BJ were ever in direct opposition, but having two differing points of view strengthened the comedy and gave the show more to talk about.

There is strength in opposition. Our show is very ‘plot driven’ – there’s a great deal of exploring to be done in the mythology of the real world and the ‘otherworld’ where half the story takes place. It’s tempting to simply create situations where we move characters from one experience to the other, illustrating to the audience how life works in one world versus the next. If, however, that was ALL we did, take the audience by the hand on a tour of an unfamiliar world, they would change their Netflix choice pretty quickly because amazing vista’s and fascinating history work in a documentary, not a fast-paced action/drama. We are given a wealth of characters to work with and we need to find compelling reasons for them to disagree and oppose each other whenever possible.

Maybe we can try some other examples…

Everyone who knows me, knows that McG’s ‘Charlie’s Angels’ is in my top 3 favourite movies. I won’t waste space here explaining why (that fact isn’t relavent to the article) but I will use it to point out a failing in conflict. The movie itself has villains and antagonists, plenty of conflict, problems to solve and obstacles to overcome, but one thing it lacks is conflict among its three leads. When Natalie, Dylan & Alex are together, the story clips along but there isn’t much that’s exciting about what they do – they are always in agreement and super supportive of each other, so while they have an objective, such as try and beat the shit out of Crispin Glover, they don’t drive the drama themselves. I know they are a team, and a desire to depict three cooperative women who back each other up rather than feed the cheap stereotype of ‘back-stabbing bitches’ is a key element here, so it functions as it should, but it still leaves the story a little flat.

As opposed to this masterpiece:

Where even the characters who are on the same side, characters who are freakin’ FAMILY, have conflict. Baby lives with his deaf step-father (I think that’s how that works) and drives getaway to not only pay back his criminal debts but also support them, and they are STILL in conflict with each other. His step-father wants him to leave the life of crime, so much so that they argue (in ASL) about it and it drives a wedge between them, and these are two characters who love and care for each other. There is conflict between each character in this film; between crime boss Kevin Spacey and those criminals he employs, between Baby and Debra (in the form of Baby’s evasion and lies) even between Buddy and Darling, the psuedo-married couple who serve as muscle for Kevin Spacey.

Making one character or another an objectionable human being is a good start, but this isn’t something that can be sustained without decent character development. Remember the dramatic triangle in ‘LOST’? Jack vs Kate vs Sawyer –

Here were three characters, none of them ‘objectionable’ (Okay Sawyer was a charming prick in the beginning, but again that was the point) who very often stood in opposition to each other due to their motivations and backstories. For 3 years (at least, some of us poor saps stayed for all 6…) we were captivated by their interactions and machinations against each other while having a hard time picking who among them was the ‘right’ one. We couldn’t because the conflicts they shared were not clear cut matters of black & white. Forget ‘The Hatch’, ‘The Swan’, ‘The Looking Glass’ or ‘The Others’ – it was the characters on ‘LOST’ that kept us watching because every week we got to see how three different personalities would approach the same obstacle with a unique perspective. For a while, it was brilliant.

Okay seriously, you want something current? Fine:

Netflix’ ‘Narcos’ does the same thing with incredible results, and I’ll use examples from season 3. (If you’re worried about spoilers, the show is based on history – Escobar isn’t in the third season, SHOCKER!) Taking cues from the ‘The Wire’ a decade previous ‘Narcos’ dramatizes actual events by adapting real life people into characters on a spectrum of gray, then forcing them to deal with each other. It’s easy to say that the Orejuela brothers are villains, ‘cuz sometimes they sure as shit act like it, but the DEA agents they have pursuing them are often depicted as being just as untrustworthy or incompetent as one might expect from a traditional foil. Furthermore the character Jorge Salcedo is depicted as one of the most moralistic of all the characters, and he’s the cartels head of security. The conflict doesn’t emerge just from the ‘good cops trying to catch bad guys’ angle – it is cultivated inside the Cali cartel itself, between the brothers, their muscle, their chief of security and their competing interests. If it was just about the cops trying to stop the drug lords the show would proceed along a rather stale A to B line, a documentary tour through facts that is as exciting to watch as ‘Ken Burns: The Drug War’… (Actually I would totally watch that – I want to hear Keith David’s smooth tones narrating a police statement about how the cartels removed peoples heads with chainsaws played over the slow pan across black & white photo’s…)

Whenever you’re looking at your work and wondering why it doesn’t land, why people are falling asleep during your readings and/or on their phones instead, or you’ve been a victim of the ‘silent pass’ yet again after sending in your screenplay, go back in and look for conflict. If everything is clipping along fine and everyone is getting along, you have a problem. Your well oiled team of professionals needs to be pulled apart and set against each other in some way. Your uber-tight best of friends need to be set at odds by the simplest of factors. You don’t need to sow dischord where there is meant to be happiness, but you need to have a reason that two characters want different things, and let that build the drama that will make your work worth reading .

Moving the audience through your plot is one thing, and it’s important. Making them care about why they are there is the real trick. You can guide anyone from one place to another by the hand and show them pretty pictures along the way, but having them invest in the characters by forcing them to have an opinion about what one character is saying/doing in opposition to the other is the real trick. When an audience has to actively think about what is being presented to them because the characters are not all in agreeance, they are entertained. That’s your job after all, to entertain.

(* Bonus blog-points to anyone who can identify the source material for the moon whale, glass palace and fat, blue moon-wookie.)

Leave a comment